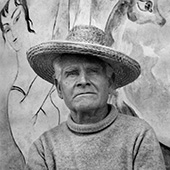

Lado Gudiashvili

The gallery of 20th century Georgian painting has been created by outstanding personalities, distinguished by their artistic merits as well as by their individual charm, and their captivating artistic perception of the world. They include individuals who introduced innovative art forms and who earned a permanent place in the treasury of the Georgia’s cultural heritage. One such personality was undoubtedly the artist Lado Gudiashvili.

Lado Gudiashvili was born on 18 March 1896 in Tbilisi, in the family of David Gudiashvili and Elizabeth Itonishvili. From an early age, he was drawn towards painting and drawing, and in 1914 he graduated from the Art School in Tbilisi with a Diploma with distinction. He then worked on several magazines as an illustrator. From1916 he took part in the expeditions organized by the ‘Georgian Artists’ and the ‘Historic-Ethnographic Society’ for the purpose of studying the architecture and wall paintings of Medieval Georgia. During these expeditions Lado Gudiashvili copied the frescos of Nabakhtevi and David-Gareji churches which were exhibited in 1917 together with the copies made by other artists in the ‘Temple of Glory’ (now the Dimitri Shevardnadze National Gallery of the Georgian National Museum). The study of monumental wall painting and the process of rationalization of this experience were to be valuable assets for of Lado Gudiashvili’s future activities and can be observed in his many creations.

The creative atmosphere in Tbilisi was especially lively in the teens and twenties of the 20th century. Situated on the crossroad between West and East, Tbilisi had its specific charm, which attractive many artists from all over the world, who also wished to escape from war. As the poet and artist Egor Terentiev wrote, ‘the train from the Maidan would go straight into Europe’. Tbilisi was a truly multi-cultural town, a melting pot for many nationalities. Here one could observe true diversity as Georgians, Azeris, Kurds, Armenians or Jews, kept to their traditional ways wearing their national costumes; at the same time one could see men accompanied by women holding European umbrellas and clad in the latest European fashion. The city’s extraordinary variety inspired many European artists. The Tbilisi of this period was visited by Sergei Esenin, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Alexei Kruchenykh, Vasili Kamensky, Konstantin Balmont, Yuri Degen, the artist and composer Alexander Korona, the composer Nikolai Tcherepnin, the artists Sergei Sudeikin, Savely Sorin and many others. Tbilisi became the city of artistic and literary unions and salons, such as the ‘Tsisperkantseli’ (Blue horn), ‘Mali Krug’ (Small circle), ‘Futuristta sindikati’ (Syndicate of the Futurists), ‘The Society of the Georgian Artists’, where a new generation of artists full of new ideas and individual creativity came together and collectively contributed to the establishment of a new era in Georgian art. These artists were the ones who tried to absorb and transfer the ideas of the art of the European avant-garde movement to Georgian reality.

These Georgian artists, together with their European colleagues, would meet and discuss matters of art in many venues in Tbilisi. The traditional places for passing time in Tbilisi were the Avlabari and Ortachala districts dotted as they were with dukhans, serving Georgian wine and delicious food and decorated with the paintings of Niko Pirosmanashvili (known as Pirosmani). The European part of Tbilisi was famous for rows of artistic cafes: the “Fantastic samikitno”, the “Ship Argo”, the “Peacock’s tail”, the “International”, or the “Kimerion”, which would host the bohemian gatherings of Tbilisi society.

Lado Gudiashvili was the soul of these artistic gatherings. Together with Ilya and Kiril Zdanevich and Alexei Kruchenykh he became a member of the Syndicate of Futurists; together with David Kakabadze and Sergei Sudeikin he painted the walls of the café Kimerion, and illustrated books about avant-garde literature. 1917-1918 were the years of his formation as an artist, the first important stage in his creative life which already showed the outstanding qualities of a talented painter.

Lado Gudiashvili’s first period was inspired by Tbilisi and mainly depicted its exotic inhabitants: kintos, karachoghels and the scenes of life of leisure and pleasure of traditional party-goers. The kintos were small scale traders in Tbilisi, famous for their cunning ways; the karachoghels were called the craftsmen of Tbilisi, who had their own rules of conduct, wore distinctive clothes, and were distinguished by their behaviour. This civic subculture became the inspiration for Gudiashvili’s paintings. Such paintings as ‘Toast in the down’, ‘Partying Kintos with a Lady’, ‘Fish Tsotskhali’, or ‘Khashi’ show his acute individualism executed with sharp expressionism. His clear rhythmic lines combined the artistic outlook of European Modernism with a new emphasis on the depiction of a human body, presented with fresh artistic outlook. Lado Gudiashvili achieved this goal with seemingly effortless flair. In his ‘Bohemian Rhapsodies’ Gudiashvili succeeded in creating totally new interpretation of the images while at the same time retaining essential individual characteristics. Only a few painters of the teens and twenties of the 20th century managed to solve these artistic dilemmas with the same success as Pablo Picasso, Mark Chagall, or Amedeo Modigliani.

It should be noted that some of the factors that led to the creation of his distinctive artistic style and which persisted throughout his long and productive career, were already present during his early period. These included (1) a deep knowledge of the methods of Georgian Medieval wall painting which contributed to the monumentality of his images and which were transferred to the linear flatness of his compositions in which he favoured vertical accents evenly distributed on the surface of his paintings. (2) He was also familiar with Persian painting which showed itself in his distinctively stylized drawings. (3) Niko Pirasmanashvili’s work was also a powerful inspiration.

In 1919 Lado Gudiashvili worked together with David Kakabadze and Sergei Sudeikin on the decoration of the café Kimerion in Tbilisi. Working side by side with Sudeikin proved to be a great experience for the young Lado. His composition ‘Stepko’s dukhan’ was a wall painting depicting the owner of the dukhan, his waiter and the counter full of fresh fish, fruit and bottles of wine. The painting was situated above the staircase of the café. The composition radiated liveliness, with exact characters and a subtle colour scheme. The artistic value of the composition was strengthened by its situation at a specific architectural point: the scene was executed in such way, and with such exact perspective, that visitors would be drawn towards it and to feel that they became participants of the unfolding scene.

In the same year the Gallery known as ‘the Temple of Glory’ hosted an exhibition of Georgian painters that included Lado Gudiashvili. The exhibition attracted a huge interest among Tbilisi society. Dimitri Shevardnadze, the director of the National Gallery, succeeded in raising funds to enable the painters to travel to Paris.

Paris in the twenties of the 20th century was the focus for young innovative painters, sculptors, poets, writers and composers. Their presence at the centre of world avant-garde art helped the young artists to widen their horizons and to increase the range of their abilities. Lado Gudiashvili remained in Paris until 1926. During this period he participated in group exhibitions in Paris as well as having his own personal exhibitions at the ‘La Licorne’ Gallery and at the Gallery of Joseph Biel. He also worked as a theatre decorator. His paintings became collectables and the art critics André Salmon and Maurice Reynaudre viewed his work.

Lado Gudiashvili returned to Georgia in 1926, but found a greatly changed artistic reality. His country had become a Soviet republic instead of the independent country he had left. He began to work as an artist for the theatre and cinema. In 1936 he created the very first Georgian animated film ‘The Argonauts’ together with the film director V. Mujiri. He also worked as a book illustrator. His oil paintings became more colourful: a sophisticated richness of gentle subtle tones replaced the subdued dark but expressive colour scheme of contrasting black and green of his earlier work. He began to be enthusiastic for the genre of portraiture, and created his own interpretation of the images in the portraits. For example, in ‘Eteri in front of the mirror’ (1940) and ‘Tamara Tsitsishvili’ (1940) he tried to capture the individual resemblance and simultaneously to transform the theme and image into a stylized and generalized artistic form.

In 1932 the doctrine of the Social Realism began to be promulgated in the Soviet Union. The main goal for art was now to serve as propaganda and to convey the ideas of the Soviet government to the masses. Soviet artists had to praise their leaders, heroes of the Soviet Revolution and Soviet workers. Such pressure left no room for the artists’ fundamental principle, namely the freedom of expression. Such an environment proved especially difficult for Lado Gudiashvili to cope with, for his main artistic asset was his spontaneity and individualism.

Gudiashvili found a solution to this problem in his inexhaustible imagination. He began to create a fantasy world based on fairy tales, historical legends and myths. He never complied with the demands of the Soviet authorities and became the symbol of an artist who resisted pressure to serve the system. From the late twenties we can see a new mood in his paintings, uncharacteristically filled with a tragic spirit and despair. His paintings ‘Destitute’ and ‘The Evil Family’ were full of reproach but at the same time empathy for human vices and wickedness.

From the 1940s Lado Gudiashvili began to draw inspiration from historical and epic folklore, creating paintings such as ‘The Legend of the Foundation of Tbilisi’ (1945), ‘Worthy reply’ (1945), ‘From the Sarcophagus at Armazi’ (1951), ‘The Devis Wedding’ (1954), and the artistic allusions such as ‘Before the Promenade’ (1941), ‘Dancing Ol-ol’ (1945), or ‘Chukurtma in a Red Hat” (1944).

In 1946, Kalistrate Tsintsadze, the Catholicos Patriarch of Georgia, commissioned wall paintings of Kashveti Saint George Church in Tbilisi to Lado Gudiashvili. This commission was one of great significance for Lado, for he could now put into practice his knowledge of Georgian architecture and monumental painting which he had obtained during the expeditions to Nabakhtevi and David Gareji. It was also a great challenge in a country with a totalitarian regime, and where atheism had been declared to be the state ideology. To fulfil the task meant that Lado Gudiashvili would have the opportunity to express his own views on the issue. Although he had been repeatedly warned about the numerous dangers to his life and well-being that might ensue should he undertake the task of painting the church, Gudiashvili nevertheless happily accepted the offer and did the job.

In Kashveti church Lado Gudiashvili depicted on the principal apse the Virgin and Child, and the Apostles, taking Holy Communion reunited against the background of the Garden of Eden. The adjacent wall was decorated with the Archangel Gabriel and an Annunciation scene. Work was soon stopped however, and Lado Gudiashvili felt the full power of the delayed censorship. He was accused of being a formalist, and was dismissed from the Academy of Art in 1948, and his membership of the Union of Painters was also brought to an end.

The wall paintings of Kashveti emphasize and illustrate once more Lado Gudiashvili’s true nature. The frescos are not only free from the doctrines of Socialist Realism, but they also do not fully follow the established iconography and teachings embodied in Medieval church paintings. The individualism of Lado Gudiashvili’s art won over the ideological restrictions.

From the 1940s, the artist began to draw sharp satirical images full of acute social criticism. This was his answer to a reality that was totally unacceptable to the artist. His uncompromising attitude made him especially attractive as a colleague and mentor for younger artists. His exhibition of 1957 at the National Gallery triggered an artistic protest, highly unusual for the Soviet regime. On 14 May 1957 the National Gallery (the former ‘Temple of Glory’)was planning to open a retrospective exhibition of Lado Gudiashvili’s paintings that included some 800 works created throughout his artistic career. On the eve of the opening of the exhibition, the censorship body decided that the works were highly inappropriate and that the exhibition should be banned. Tbilisi society was not aware of the ban, and people had begun to gather outside the National Gallery fully expecting to see the exhibition. When the public had learnt that the doors of the Gallery would not be open for them, the younger artists forced their way in and the public followed. Eye-witnesses recall the great impression which the exhibition had on them. The art of Gudiashvili demonstrated that it was possible to stay true to oneself as an artist and to pursue individualistic artistic values even when living in a totalitarian and restricted environment. This exhibition became one of the main inspirations for the generation of the 1950s, who would set in motion post Stalinist liberalization in art.

From the late 1950s, governmental control of art had been slightly eased, and this had a beneficial effect on Georgian art. Lado Gudiashvili returned to his earlier style, and his works of the sixties and seventies display the artist’s preference for line rather than colour. The artist abandoned his sharply expressionistic manner, and instead his work of this period is full of articulate elegance and musical fluidity. His ‘Woman with Red Gloves’ (1964), his ‘Fortune Teller’ (1969), or his ‘Anano with Flowers’ (1974) show that the artist’s fantasy could at last breath freely. Lado Gudiashvili was able to transform impressions inspired by his contemporaries into a journey in time and space where his images would acquire a new life in his fantastical reality.

Book illustrations and theatrical decoration are worthy of a separate chapter among Gudiashvili’s artistic achievements. He was active in both spheres throughout his long life. The most outstanding works among his book illustrations are undoubtedly his illustrations for Shota Rustaveli’s ‘The Knight in the Panther Skin’ on which he worked between 1931 and 1966; the ‘Wisdom of Lies’ (1958) and ‘Balavariani’ (1962).

Lado Gudiashvili died in 1980 leaving hundreds of works: oil paintings, graphics, book illustrations and theatre and film designs. He had dedicated almost 70 years of his life to his art and thus became a shining star of the Georgian artistic heritage. Lado Gudiashvili’s grave is situated on Mt. Mtatsminda where he rests in the Pantheon for writers and public figures.